'The Outer Worlds 2': the space RPG where ambition finally reaches satire

'The Outer Worlds 2' opens with a clear promise: you're in charge here, but you'll have to live with it. This time, the game throws you into Arcadia, a lost colony on the edge of space that is being torn apart—literally—by space-time rifts opening up amidst the jump systems.

Your character, known as "the Commander," is neither a mythical hero nor the chosen one of prophecy. He's an envoy of the Earth Directorate, a kind of central authority that, more than saving lives, wants to stabilize its own interests. You technically arrive to "fix the problem," but it quickly becomes clear that the problem is political, economic, religious, and existential all at once. That's the tone of the game: corporate science fiction, dark humor, and decisions that almost always feel dirty.

Arcadia is not Halcyon. This isn't a simple "we're back on the same planets with a new villain." Obsidian changes colonies, changes power players, and changes the focus of the story. Arcadia is a chessboard with multiple factions that aren't waiting to see what you do: they're already at war. You have mystical cults convinced that dimensional rifts are the gateway to some kind of cosmic enlightenment. You have private conglomerates that see these rifts as potential trade routes, literally new highways for controlling traffic, goods, and debt. And you have "law enforcement" forces that want to seal everything off in the name of stability, even if it means brainwashing anyone who isn't in line. The interesting thing is that the game doesn't push you to choose the "right side," because there isn't one. They're all broken. What it asks of you is to understand how comfortable you are with that brokenness, and how far you're going to take it.

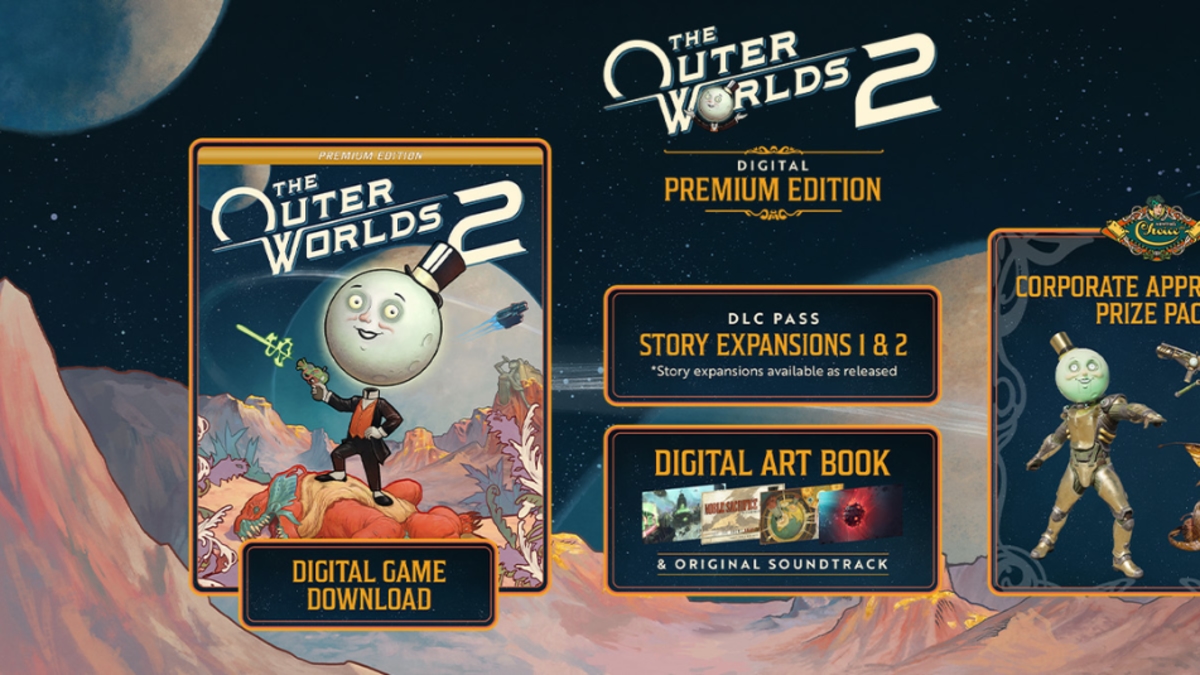

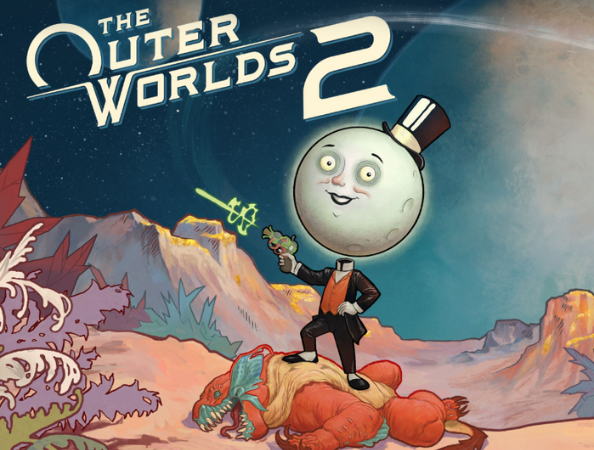

The Outer Worlds 2 Photo: xbox.com

From the very first issue, it's clear that Obsidian is much more confident in its own universe. The satire is still there—the mockery of extractive capitalism, empty corporate rhetoric, and executives who sell genocide as "process optimization"—but it's not just a joke. The writing now has a sharper dramatic edge. The conversations aren't just meant to make you laugh, but to make you uncomfortable. The factions have reasons, even if those reasons are morally revolting. The result is that the world no longer functions simply as a caricature of "bad corporations," but as an ecosystem where every group is dangerous in its own way, and where any alliance you form leaves scars.

This is underpinned by the most important aspect of 'The Outer Worlds 2': real freedom. Not just decorative freedom. The structure remains that of a first-person RPG with open worlds and large areas to explore, but now those areas are even larger, with more routes and more solutions. Main missions are rarely linear. You're sent to break in, steal, sabotage, persuade, make someone disappear, or find out what the hell happened at a certain facility… and there's almost never just one way to do it. You can go in guns blazing. You can hide, sneak in, disable defenses. You can manipulate dialogue and get someone else to do the dirty work. You can resolve an entire conflict without firing a shot if you build a character geared towards negotiation, deception, or social engineering. Or you can go to the opposite extreme: build yourself into a mobile violence machine. The game accommodates all these approaches, and more importantly, it responds to them.

That "react" is what sets it apart from many RPGs that promise freedom but ultimately disguise the fact that everything ends up the same. Not here. Here, your companions aren't there to applaud your every move. You have a team with strong personalities, each with their own loyalties, red lines, and moral interpretation of what's happening in Arcadia. And if you cross certain lines, they'll tell you. They might confront you, give you uncomfortable lectures, or even leave you. They might also admire you, of course, but that admiration is almost never free: it's because you're validating their worldview. This kind of internal friction makes traveling with others feel less like carrying around talking ornaments and more like building (or destroying) real relationships within a crew that doesn't always want the same things you do.

The other big leap is in your own character. Progression is no longer just about racking up points and calling it a day. Here, the entire system revolves around strengths and weaknesses that you consciously accept. You can gain powerful advantages, more aggressive social skills, combat upgrades, more precise hacks, but the game exacts a price with flaws that become part of your identity. You fear certain types of enemies because you've nearly died fighting them multiple times. You make poor verbal choices under pressure, and that becomes a permanent disadvantage in fast-paced dialogues. You're physically fragile in exchange for intellectual brilliance. The result is that your "build" is no longer just a statistical template; it's a playable psychological profile. And yes, that profile opens doors that another version of you would never see, but it also closes others forever. Obsidian pushes you to accept that you can't be good at everything, and that defines the tone of the journey. It's not about a perfect hero saving the galaxy. It's about someone very specific, with very specific flaws, trying to navigate a hostile environment.

The Outer Worlds 2 is the sequel to Obsidian Entertainment's award-winning first-person RPG. Photo: xbox.com

In combat, the best news is that shooting finally feels good. The first game had the heart of an RPG but the hands of a sluggish shooter; that's been fixed here. Weapons respond powerfully, the impact of each hit feels more solid, and moving through the chaos is no longer clunky. You can slide for cover, reposition yourself, take advantage of special abilities, and use the famous "tactical time" to slow down the world and target weak points. What used to be "shooting because you have to in order to advance the story" is now genuinely fun. And that matters, because the game lets you complete missions stealthily or diplomatically, but it doesn't shy away from combat when everything explodes. Even visually, the reload, recoil, and weapon handling animations no longer look like they were copied from a cheap prototype, but rather from a shooter that understands rhythm.

The overall scale has also grown. 'The Outer Worlds 2' is bigger in almost every way: more areas to explore, more side quests with real consequences, more gear to try out, more situations you won't see if you play "straightforward." The main campaign is large enough to rival the biggest RPGs on the market, and with the side quests, it easily adds up to several dozen hours. The valuable thing is that this expansion doesn't feel like filler. Many optional missions aren't "go there and get this," but rather small moral tales: a corporation that wants to "optimize" an entire community at the cost of erasing its free will; a cult that becomes convinced that the collapse of reality is a divine sign; a settlement torn between submitting to survive or dying free. These side stories don't orbit around the main mission; they intersect with it. A decision made in something that seemed secondary can come back to haunt you later, with consequences that affect your reputation or even who trusts you in critical moments.

Visually, there's a clear leap. The first installment already had its own identity—that blend of corporate retrofuturism, gritty neon, and optimistic propaganda selling labor exploitation as "opportunity"—but technically it felt limited. Not here. The game jumps to more modern technology, and it shows in everything: more natural lighting (or as natural as an alien sky with two giant moons can be), more defined materials on armor and industrial surfaces, denser atmospheres, landscapes that open up to the horizon with cities gleaming in the distance. It doesn't aim for photorealistic hyperrealism: it remains stylized, exaggerated, almost pulp. But now that style has muscle. On PC and new consoles, the world has an image clarity, a richness of color, and an architectural scale that the first title simply couldn't achieve. This engine also opens the door to specific things like more believable reflections, volumetric fog with depth, and particle effects that make certain battles—especially those involving energy weapons—look more chaotic and cinematic.

Yes, there are some debatable points. The start can feel slow. The game takes its time setting up the political landscape, introducing you to Arcadia, and explaining why the time rifts actually matter. This initial pace might clash with players who crave immediate action. There are also moments—especially during missions to clear enemy bases—where certain enemy types start to become repetitive and lose their element of surprise. And while the combat is much improved, there are still situations where you feel the enemy AI is acting strangely or getting stuck in cover. In short: it's not perfect. But it doesn't pretend to be perfect either. What it offers is consistency.

The most important thing is this: 'The Outer Worlds 2' no longer feels like "Fallout's space cousin trying to prove it can parody capitalism better." It feels like its own thing. It feels like a franchise that has found its voice. Arcadia has conflict, it has cynicism, it has biting humor, and it has consequences. Your companions aren't human shields with witty dialogue; they're people with boundaries. Your choices aren't cosmetic; they're decisions that blow some doors open and seal others shut. And the studio, Obsidian, which has always thrived on putting the player at the moral center of broken worlds, finally has the technical budget to make that world look, sound, and feel as good as what it writes.

What remains in the end is not just a good narrative RPG. It's a game that understands that an interesting universe isn't enough if moving around it is awkward; that understands that good gunfights don't matter if the choices are meaningless; that understands that satire loses its impact if it never strikes a nerve. The Outer Worlds 2 brings these layers together and makes them work simultaneously. And yes, it's bigger, longer, and more visually stunning. But what truly matters is that, for the first time, that ambition is completely under control. Obsidian didn't just build another planet for you to explore: it gave you a broken world and asked you what kind of force you're going to be within it.

eltiempo