Two million shells enclose the story of human ambition: a journey of luxury, beauty and power.

“Look, here, look at this carefully,” says Fernando García as he opens his hands and reveals a treasure. “This is proof that human beings, in reality, don't invent anything, but rather copy it from nature,” he adds. Between the biologist's fingers , a perfectly round shell gleams, a spiral in the shape of a tiny staircase that descends upon itself until it disappears into the center of the shell. “It's an impeccable golden ratio,” he notes before returning it to a shelf crammed with other shells. This one was from a sea snail—of the species Architectonica maxima— and is now part of the malacology collection of the National Museum of Natural Sciences (MNCN) in Madrid, where García works as an archivist.

Malacology is the branch of zoology that studies mollusks, a highly diverse group of invertebrates that includes snails, octopuses, and clams. And, of course, their shells. The second floor of the Madrid museum houses one of the largest collections in the world, organized into three major ecosystems: marine, freshwater, and terrestrial. There are nearly two million specimens in total.

“It all began in 1771,” explains Francisco Javier de Andrés, also curator of the MNCN archive. It was then that King Charles III received the donation of Pedro Franco Dávila’s collections of natural specimens, which were used to found the Royal Cabinet of Natural History, the seed of the current museum. Since then, the shell collection has continued to grow, fueled, at first, by Spanish scientific expeditions to the Americas—especially Cuba—and the Philippines, which returned laden with exotic species , turning the archive into one of the most comprehensive on the planet.

The pieces are preserved dry and also in fluids, jars filled with alcohol that preserve the bodies of the mollusks that inhabited those shells and now rest in a dark room in the museum's basement. Some have been there for centuries. The oldest piece is a Pinctada margaritifera , also known as the black-lipped pearl oyster. It was collected in 1758. "We believe it may have belonged to the Royal Cabinet of Natural History since its founding," says De Andrés.

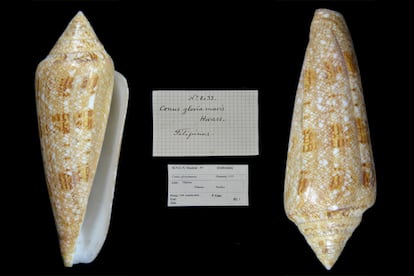

The most beautiful of all shellsMany of the shells are steeped in myths and legends . Between the aisles, García stops in front of a long shelf and decides to reveal one of these secrets. “It’s one of my favorites,” he says. What he’s showing is a Conus gloriamaris, brought from the Philippines in 1777. “The region is a shell paradise because it’s a tropical archipelago that’s highly fragmented, producing currents with a lot of calcium carbonate, the raw material from which mollusks make their shells,” De Andrés is quick to explain.

Since the 18th century, the Conus gloriamaris has been the most valuable and coveted snail on the planet. “It has been said that it was not only the most beautiful and rare of the Conus , but also the most beautiful of all shells ,” wrote the Spanish naturalist Florentino Azpeitia in a 1927 scientific publication. A close look is enough to understand why: a stylized, conical silhouette measuring 15 centimeters covered in a delicate network of dark lines on a yellowish background that looks hand-painted.

Until 1949, only 22 specimens of Conus gloriamaris were known worldwide. In 1927, its price reached 6,000 French francs. In 1934, MCNC obtained its own specimen from Azpeitia's own collection. Word of mouth has it that before the Civil War, and for years, the museum kept the specimen in a bank vault to prevent it from being stolen. "This is a fact we have through oral tradition here at the museum because we haven't found any documents to prove it, but it makes sense to avoid temptation," De Andrés clarifies.

This isn't the first time the value of a shell has been equated with that of a precious metal. Throughout history, various cultures have used shells as a form of payment. The best-known example is cowrie shells, which were used as currency in Africa, Asia, and some Pacific islands. These shells were valued for their durability, portability, and beauty. Their use as currency is explained by the fact that they were relatively scarce, easy to transport, and difficult to counterfeit, fulfilling many of the functions we understand as money today.

Artistic inspirationThe collection is transformed into a labyrinth of stainless steel cabinets, fireproof and hydrophobic, designed to withstand fires and floods. Each shell is stored in an acid-free polystyrene plastic container. "Previously, they were housed on wooden shelves, which released vapors that, combined with the temperature and humidity, were capable of dissolving the calcium carbonate in the shells," says García. The room is not air-conditioned, but they hope to install equipment soon to maintain a constant temperature of 21 degrees Celsius and recreate an optimal ecosystem for preservation.

“Tell me, what does this remind you of?” García asks, taking a pale pink shell in both hands and extending it forward. “It looks like porcelain, right?” He’s holding a Harpa major , and yes, it could easily be mistaken for the finest porcelain. “Mollusks have historically served as inspiration for various human disciplines,” the curator adds. Fashion, architecture, ceramics, and even dance have used the shapes, colors, and textures of snails to compose or design works of art.

Camouflage colorsAt the end of the tour, the scientists head to a small room. In the center, there's a wooden table filled with small snails and papers. "This belongs to a colleague who's researching a topic for his thesis; that's another function of the collection," García points out. With a careful gesture, the scientist moves the materials aside to make room for what he's truly interested in displaying. "This is where the terrestrial specimens are kept," he comments. Now, the collection begins to show a different kind of exoticism.

One example is Papustyla pulcherrima , a gastropod that lives in tropical rainforests and is endemic to Manus Island (Papua New Guinea). It's a small, bright green snail that resembles a gemstone. "Shells," García begins, "tend to take on the colors of their environment; that's why marine shells have shades like sand, but in the case of terrestrial ones, things are different." Each shell is a living architecture that the mollusk builds throughout its life, secreting minerals and proteins. In the case of Papustyla, it's not known for sure where it gets its distinctive color, but it's suspected that it processes plant-derived compounds and, using its metabolic machinery, transforms them into the green pigment that is deposited on the shell and gives it its color.

“It's all about camouflaging yourself so you don't get eaten,” explains García, picking up a new shell. The Liguus fasciatus is a small, elongated, conical snail with a thin, smooth, and shiny tip. Against a pearly background, brightly colored stripes—green, yellow, brown, pink, or even purple—unfold irregularly around the spiral, creating unique patterns.

After viewing a good portion of the collection, one question seems unavoidable. "Which is our favorite piece? Well, for us as biologists, talking about a favorite piece is very complicated: they're all emblematic," García adds.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F765%2F13d%2F198%2F76513d198768d58b6df92a0c7e69370a.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F75d%2Fa0b%2Fba7%2F75da0bba7997b3075ff709deac7988ba.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F64f%2F62d%2Fe01%2F64f62de01d40c69bc858c01c4949c44b.jpg&w=1280&q=100)